Banking on Land: Property in a Post-Industrial Age

- Rustopolis

- Apr 17, 2022

- 7 min read

Updated: Jun 6, 2022

One of the greatest challenges faced by cities with large portfolios of abandoned buildings and vacant lots is what to do with it all. Maintaining these properties is expensive for any municipality, let alone those with dramatically reduced tax bases. Vacant lots have to be mowed and kept clear, or they will become overgrown. Abandoned buildings lurch into decay, and have to be torn down in order to save municipal maintenance costs or to ensure public safety. Water mains may freeze, expand, and rupture with the changing seasons, and sidewalks buckle and crumble when street trees are not maintained.

Multiply these costs by thousands of properties, and the scale of the challenge for municipal governments becomes overwhelming. Because U.S. cities cannot run operational deficits and rely on the taxation of property for a sizeable portion of their revenues, the flight of population and capital places severe constrains on municipal budgets. Large portfolios of abandoned properties add substantially to the debit side of municipal budgets, so cities seek external support from State and federal governments. Detroit's Land Bank Authority, for example, received $265 million from the federal Hardest Hit Fund program in 2014, which it used to demolish 15,000 buildings--about 40% of the city's total. St. Louis routinely uses federal Community Development Block Grant funds to maintain vacant properties, and in 2018-2019 doubled the allocation for demolition to $3.6 million (City of St. Louis 2018). Beyond demolition, however, the key challenge for these cities is how to dispose of vacant properties as rapidly, cheaply, and efficiently as possible.

In the Anglo-American legal tradition, when we buy property, we are primarily purchasing the land (the real estate) upon which there may be some kind of improvement: a farm, a house, a factory, for example. Properties accumulate equity over time in the form of public and private investments, some of which are direct (constructing a house, painting a fence, installing electricity), others of which are ambient 'externalities' (public investments in schools, parks, street trees, mass transit, for example) (Fischel 1980; Boyle and Kiel 2001; Faber and Ellen 2016; Saengchote 2020). In order to remain viable, properties require periodic maintenance and upkeep to the varied components over time. Many properties go through valuation cycles, where their exchange value rises or falls. When private or public capital is withdrawn, either from the property itself or from the surrounding area, the exchange value of the property declines, until it cannot be sold or is no longer desirable to retain. At that point, it may be vacated, its improvements abandoned. Such is the situation in which hundreds of thousands of properties have fallen in post-industrial cities across the Northeast and Midwest of the United States (Accordino and Johnson 2000; Anderson and Minor 2017).

Within this orthodox property model, abandoned structures and vacant lots appear as singular, disconnected parcel geographies--each tied to an individual tale of woe. This is brought home dramatically in the efforts by municipal governments and state-chartered land reutilization authorities to re-marketize abandoned and vacant parcels, to convert land back into property in order to bring people back and to generate much-needed tax revenue. Detroit, for example, maintains an extensive web site Own it Now, operated by the Land Bank Authority. The site functions much as any real estate listing service, with tiled images of houses and lots arrayed in a grid on the screen and accompanied by information on the selling price, location, and square footage.

Each image in the grid opens onto a page with multiple images of the property and as much information as is available about its age, utility connections, taxes and closing fees. The Land Bank Authority has only listed those properties for which title has been cleared--an often long, tedious, and technical process requiring the curative power of the local state to secure legal documents and rulings.

The site also includes a link to resources such as a handy "Property Walk Through Guide" that features checklists, inspection tips, a glossary of terms (e.g.--lintel, soil stack, stringers), and updated information about estimated per-square-foot repair costs in the Detroit area. One of the most common and important alerts included on many of the listing pages pertains to water connections:

The Detroit Land Bank Authority has no knowledge of the condition, connection, or operability of the water service line that would normally connect this property to the water main, the line may be severed, damaged, or otherwise inoperable. Obtaining water service to this property may be a significant challenge and cost to the purchaser, in addition to the other challenges and costs of rehabilitation. Further, the water service line may be a lead line that requires replacement at the homeowner’s expense.

The site comports as an ordinary real estate walk-through, with a grid of images of individual properties each linked to a page with details and additional images. The base page for each property includes an image slider, except that instead of the staged scenes typical of commercial real estate web sites, Own it Now images reveal exterior and interior spaces in varied states of disrepair. This usually involves some combination of broken or missing windows, water or fire damage, collapsing walls, overgrown and debris-filled yards.

Typically the houses have been stripped of interior copper wire and pipes and any other valuable materials. In the older homes, plaster walls have moldered and decayed, sloughing off to expose the lathe beneath. Many have grasses or tree saplings established around the eaves, roofs, and porches, and some even have vines growing into the interior. Water in particular can exert a high degree of damage by rotting support joists and rafters. In most cases, the exteriors and interiors have become dumpsites, with furnishings, clothes, children's toys, food, boxes, and other items left by the last tenants interspersed with waste dumped by others subsequent to abandonment.

This house in the Gratiot Woods neighborhood provides a case in point. Located at 4749 McClellan, it sits on the west side of a block that contains 17 buildings, four of which are boarded up, and 15 vacant lots. The two-story house built in 1923 features 2208 square feet, a large front porch, three bedrooms and two baths, and a usable attic. It appears that at some point it was subdivided into a duplex, evidenced by the two front entrance doors.

Although the Land Bank Authority has declared the building to be structurally sound, the labor and cost of renovation would be very high (see images below). The front porch is in an evident state of collapse. All interior rooms are in varied states of disrepair, with missing windows and accumulated debris scattered throughout. Significant amounts of plaster have mouldered and crumbled away, and ceilings have begun to fall, even to the point of exposing rooms to the exterior eaves. Nevertheless, the property is available for $1000 plus $827.25 in closing costs, recording feels, tax certification, and title insurance.

The new owner has two main options for the dispensation of the property. She rehabilitate the property for personal occupancy or to rent to others, or she can demolish the building (DLBA 2020). Either option must be completed within nine months of purchase, or the owner risks default on their agreement and a return of the property to the Land Bank Authority. Rehabilitation requires substantial investment to ensure the structural integrity of the building; clear the lot and interior of debris; repair walls, ceilings, and floors; install insulation and plumbing; rewire for electricity; and re-establish connection to the city's water system. All of this must be done according to the city's building code. The alternative of demolition is also a costly and involved procedure. The owner must not only clear the building and lot, she also has to abate any lead and asbestos that might be present, as these can become aerosolized and scattered when disturbed (Rector 2022, 214–15). Once the lot is cleared, the owner is also required to excavate and backfill the site. The Authority has been obligated to pursue legal action against unscrupulous companies that enter into contracts for demolition, but cut corners by burying debris on site in violation of environmental laws and building codes (DLBA 2020).

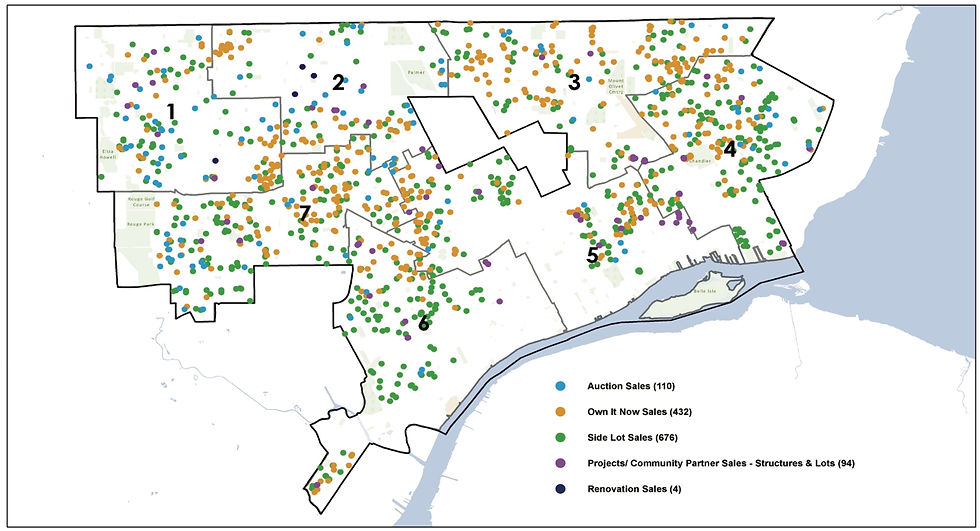

Detroit Land Bank sales during the first quarter of 2020.

The Detroit approach is one that has been emulated by other cities. The Land Bank Authority has a daunting remit for the dispensation of tens of thousands of acres of disinhibited land. It has devised a slow, incremental, and stepwise set of procedures for doing this. The Authority's Own it Now site, for example, is a well-designed tool for reconfiguring this land into property for re-circulation on the market. As of 2020, the Authority owned 89,476 properties, including 23,333 abandoned buildings and 66,148 vacant lots. During the first quarter of 2020, the Authority sold 600 properties and closed 542, both through auctions and the Own it Now web site (see figure above). Cumulatively, the Land Bank Authority has sold 21,708 properties since its inception, including 13,316 side-lots to adjacent homeowners (DLBA 2020). Responsibility for the demolition of properties, however, has been transferred back to city agencies (Ferretti 2021). In many ways, the Own it Now web site functions as a kind of archive, and each parcel listed is an artifact laying in repose in this archive of land. What this archive does not reveal is the broader context; the individual properties appear dissociated from, and even obscure, the vast expanse of vacancy and abandonment in which they are situated, and the long legacy of racial capitalism that produced the archive in the first place.

NOTES

Accordino, John, and Gary T. Johnson. 2000. “Addressing the Vacant and Abandoned Property Problem.” Journal of Urban Affairs 22 (3): 301–15.

Anderson, Elsa C., and Emily S. Minor. 2017. “Vacant Lots: An Underexplored Resource for Ecological and Social Benefits in Cities.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 21 (January): 146–52.

Boyle, Melissa, and Katherine Kiel. 2001. “A Survey of House Price Hedonic Studies of the Impact of Environmental Externalities.” Journal of Real Estate Literature 9 (2): 117–44.

City of St. Louis. 2018. “A Plan to Reduce Vacant Lots and Buildings.” St. Louis: Office of the Mayor.

DLBA. 2020. “City Council Quarterly Report, 1st Quarter FY 2020, The Detroit Land Bank Authority.” Detroit, MI: Detroit City Council.

Faber, Jacob W., and Ingrid Gould Ellen. 2016. “Race and the Housing Cycle: Differences in Home Equity Trends Among Long-Term Homeowners.” Housing Policy Debate 26 (3): 456–73.

Ferretti, Christine. 2021. “Federal Watchdog Finds $13M in ‘unsubstantiated Costs’ in Detroit Demo Effort.” The Detroit News, June 28.

Fischel, William A. 1980. “Externalities and Zoning.” Public Choice 35 (1): 37–43.

Rector, Josiah. 2022. Toxic Debt: An Environmental Justice History of Detroit. Chapel HIll, NC: UNC Press Books.

Saengchote, Kanis. 2020. “Quantifying Real Estate Externalities: Evidence on the Whole Foods Effect.” Nakhara : Journal of Environmental Design and Planning 18 (June): 37–46.

Comments